A Congolese Classification of Magic - I

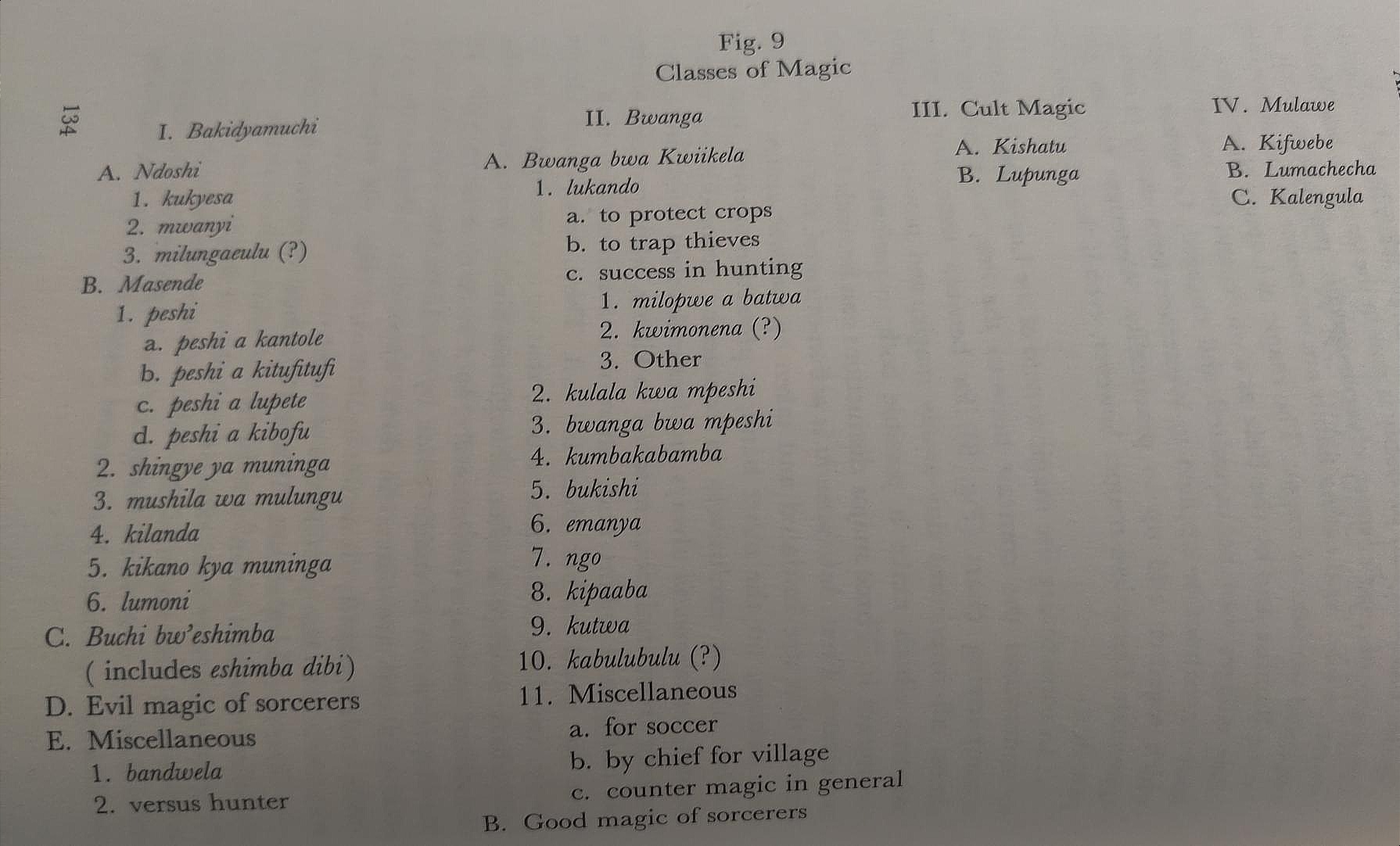

I sometimes hang around worldbuilder spaces (I know, I know) focused specifically on magic and a thing that I've seen come up a fair amount is the question of classification. You're probably pretty familiar with the sort of topics discussed if you're looking at this, but an interesting variation that I stumbled across recently was a good-natured debate concerning the dominance of what we could annoyingly call something like ~neo-western paradigms~ when folks try to set up more structured magical systems. There's definitely merit to at least broadened forms of this point, so I thought that providing a guided tour through an ""out there"" example of a real-world system for classifying magical practice might make for some good clean edifying fun. I apologize in advance for the bad photos, I typically prefer to use PDF screenshots but this book hasn't been digitized yet and hunching over a desk with an old phone creates utilitarian results at best. Behold! -

from Alan Merriam's An African World: The Basongye Village of Lupupa Ngye

Merriam's research (though it really should be called the Merriams' research - Barbara Merriam was closely involved in collecting notes alongside her husband and did much of the excellent photography) was completed during the last year before independence, finishing up right around June 1960, but the finished book is definitely part of the terminal colonial/early post-independence golden age of revisionist ethnographic and historical research in much of the continent's interior. It was a brutally short renaissance, cut down well before its prime by intense squeezes on the fledgling university programs devoted to the craft and (often instigated, always contingent) instability in the many of the new countries concerned. Even this book was intended to be a relatively concise introduction to the thought-world of Lupupa Ngye's Basongye to prepare readers for a future two volumes on the music and art of the Songye along the silver tributary. Optimistic times. To this day, An African World remains the only major inquiry into Songye spirituality and a core source for reconstructive work on precolonial lifeways in the Southeastern Congo.

It's worth questioning just how much of this was Merriam filtering the reports of his informants through a prism that forced the magical practice of the Lupupans into a more familiarly structured format, but tbh, I'm not overly worried here. Merriam dutifully reports his confusion at the placement of some elements and the vociferous responses of informants when asked if they meant to classify certain magics elsewhere, which to me implies that the whole of it isn't likely to have been cooked up by the man as an organizing tool. In any case, we don't have much else to work with, as mentioned above. Even Merriam couldn't get information on certain practices or formulas, since there were no fully-activated sorcerers (munganga) left in Lupupa Ngye by the time he visited.

A Few General Notes

Merriam outlines three key distinctions that can be made between the first two classes, to which I have added a fourth and fifth at the top for overall clarity.

- Data collected from Lupupa Ngye can't be generalized to all Basongye. Songye identity was a "dynamic, ephemeral phenomenon" in precolonial Kongolo, likely crystalized by the Luba Empire's attempts to set up new (more vertical) hierarchies upon arrival, and it's not even clear where to draw lines between fire king Bùki Kansimba's eastern Baluba conquerors and the Basongye they blended with.1

- The majority of Lupupan magic revolves around the first two classes: bakidyamuchi and bwanga. "Cultic operations" and the formal mask societies are relatively recent introductions into Songyeland from elsewhere in the Belgian Congo, largely arriving during the wave of healing movements that periodically swept the colony in response to immense societal pressures.2

- Bakidyamuchi is focused on actions that are initiated against something. Bwanga is typically reactive - whether countering action-oriented magic or providing some other protective service.

- Bakidyamuchi always involves some sort of harmful intent, ranging from malicious mischief to killing, while bwanga counters this malignant intent and, where it is action-oriented itself, is a force for harmony.

- Bakidyamuchi almost always involves individual action, that is, it is undertaken by an individual; bwanga is usually performed for the individual, sometimes communally, by a sorcerer/munganga.

A friend who I discussed this with pointed out that "directed-offensive-malevolent-individually created vs counter-defensive-helpful-provided feels intuitive and familiar." Big agree, of course, even including the weird edge cases like lumoni magic here or others we'll see in Class II/bwanga.

Class I - Bakidyamuchi

Witchery (Ndoshi)

The Killing Crafts (Masende)

- Peshi rituals all center around killing people with lightning, a pretty common concern in occult traditions globally. Lightning is fucked. The oldest form is peshi a kantole and involves killing and burning a kantole (a forest robin/Stiphrornis - the greatest birdwatchers of all time, the Mbuti, have given these guys the delightful name tungulubei) alongside some other components. Gathering the ashes into a packet and speaking the name of the victim into it will call a small black cloud to you. Greet it politely and tell it who you want to die - the cloud will do its best. The other forms of peshi are variations on this basic formula. Peshi a kitufitufi adds a crushed kitufitufi beetle to the package - it's slower-acting than peshi a kantole but ensures a kill or torched dwelling if it acts. Peshi a lupete requires the ritual destruction of a special sort of knife, which is added to the usual ingredients. The resulting mixture is then spread on a different knife, allowing for finer control over the lightning strikes.

- Needle To Murder Someone (Shingye ya Muninga) is a classic case of sympathetic magic. The sorcerer jabs a consecrated needle into a person's footprint to kill them, sometimes even immediately. Word to the wise, store your souls in a fingernail and avoid the embarrassment.

- Ask of the Mulungu/Kilanda (Mushila wa Mulungu/Kilanda) involves going to a mulungu tree or kilanda tree to request that it imbue its bark with killing power, burning some, then using the ash as a magical trap. Spread the powder across their doorstep, and when they next walk across it, they instantly die or swell horrifically from the feet up before dying (respectively.)

- I'm gonna let the book speak for this one:

- Lumoni is the strangest of the masende rituals - to gain this rare power, munganga must invert the vessel of power collection inside themselves, rendering them incapable of utilizing either masende or bwanga but granting the ability to sense if a masende ritual is in progress anywhere over a pretty large area. Wielders of lumoni were respected for their skill as arcane watchdogs but Merriam's informants pointed out that it was unlikely that a sorcerer would destroy their own ability to work magic. It was usually children of sorcerers, forced to awaken their skills early by the threat of attacks from rival munganga, who became lumoni users when the danger passed. While this seemed like a protective art to Merriam, the Lupupans placed it under this category since to gain it you must first have been initiated into a killing art, with the murder of family members that requires. A weird parallel to this can be found among Tamang ritual practitioners from Nepal, where prospective shamans who are rejected as students by the monkeylike mountain god(s) called ban jhakri gain a sort of clairvoyance in place of the powers they expected to recieve.3 Not much to add on that, just a cool similarity.

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

This is fascinating. I am going to have to try to get a copy of your main source! I agree with your assessment of lightning; it is, indeed, fucked. The idea that kinslaying is a pre-requisite for sorcery is incredibly powerful, and I think, regardless of culture, easy to conceive of - "That guy killed his brother, who knows what else he is capable of, better stay the fuck away from him." Also the idea of a poison of relationships is really interesting and something we have probably all seen at one point, but that I never associated with sorcery, though it makes all kinds of sense.

ReplyDeleteI really want to hear more about the "carving out" process used to become a witch and the "Tall Thin Ones." Talk about the ambiguity being powerful, not knowing much about either of these really makes the ol' imagination engine go nuts!

Heya, Blackout! Thanks for checking this out! The good thing about Merriam's "An African Village" is that it's by far the most reasonably priced of the out of print/undigitized 60s-80s classics of Central African ethnography available. Lots of interesting things in it - Songye religion (Merriam also wrote a paper on this which is somewhat easier to find), farming practice, sexuality (including genderqueer people called kitesha), and even a calendar + average daily schedule section. Big agree on the kinslaying - along with the poisoning of relationships, I feel like there's defo a strong current of social horror emphasized in Lupupan Songye interpretations of bakidyamuchi that works really well and can be ported to other settings. On the magical practitioners post, I promise it's coming! Been distracted by *New Thing* brain, but it'll be right up after the concluding classification post looking at the categories of cultic magic and mask magic together. I think the witches/bandoshi in particular are a really interesting spin on the familiar "witch as outcast" and have some weirdo powers, so I hope it meets the unintentionally heightened expectations. ^_^

Delete